Ito Jakuchu (1716–1800) was a painter who flourished in Kyoto during the Edo period.

A young man from Kyoto who prefers a life of seclusion.

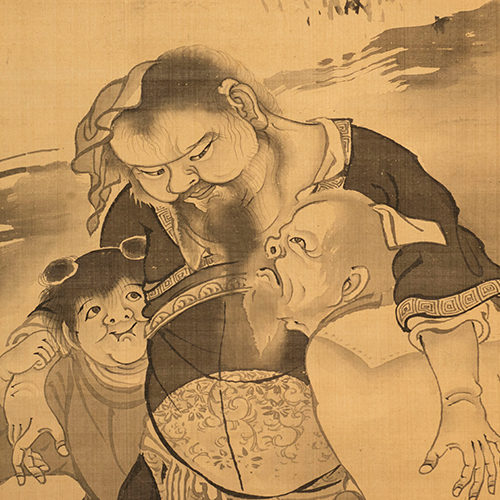

Jakuchu was born as the eldest son of the vegetable wholesaler family “Masugeng” in Kyoto’s Nishiki Market. According to Daiten, the head priest of the Sōkokuji temple, who had a deep connection with Jakuchu, it is said that Jakuchu was a man without much interest. Despite being the heir to a Kyoto merchant, he did not pursue academic studies, was not skilled in calligraphy, and did not engage in any hobbies or activities. He also seemed to have little interest in women and remained unmarried throughout his life.

At the age of 23, upon his father’s death, Jakuchu inherited the family business and became the head of Masugeng, but it seems he wasn’t inclined towards commerce. According to Daiten, Jakuchu actually preferred a reclusive lifestyle, dedicating himself solely to painting. While he tended to avoid people, he was gentle towards animals. Daiten recalls an anecdote where Jakuchu felt sorry for sparrows being sold in the market and bought dozens of them to release them in his own garden.

Jakuchu was not interested in any other hobby or art, but the only thing he found was painting. Jakuchu’s name is taken from a passage in the Lao Tzu Dao Ching, which says, “The great waxing and waning of the young never ceases its use” (something that is greatly satisfied may seem empty, but its work never ceases), and Jakuchu may have appeared to others as an “empty” person, not interested in the pastimes that most people enjoy But in reality, he had something in his heart that would last for generations to come.

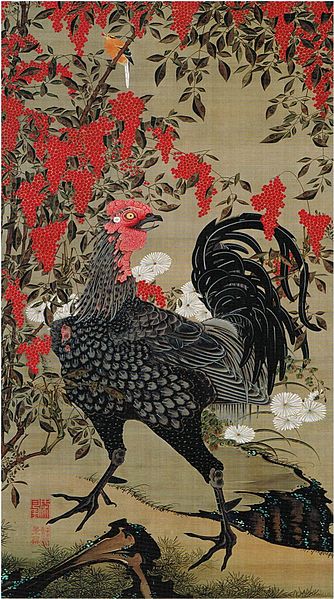

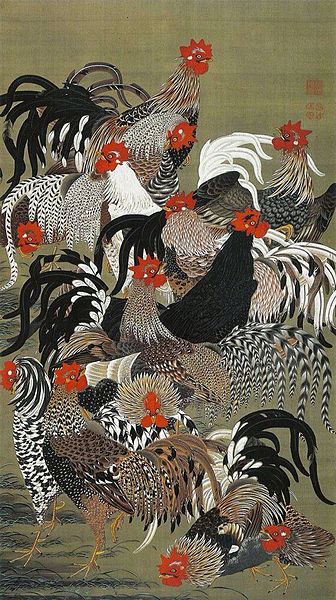

Jakuchu’s family business was a wholesale store that provided a place for producers and merchants to do business, and the land rent allowed him to devote himself to painting. Jakuchu, who wanted to become a painter, first learned the techniques of the Kano school, which was the mainstream at that time, but he realized that even if he mastered the techniques of the Kano school, he would never be able to go beyond its boundaries, so he spent his days visiting temples in Kyoto and showing them Chinese paintings that were in their collection. In his early works, we can see the influence of the Kano school and Chinese paintings, but after learning enough from the paintings of his predecessors, Jakuchu eventually began to look to real plants and living creatures as models for his paintings.

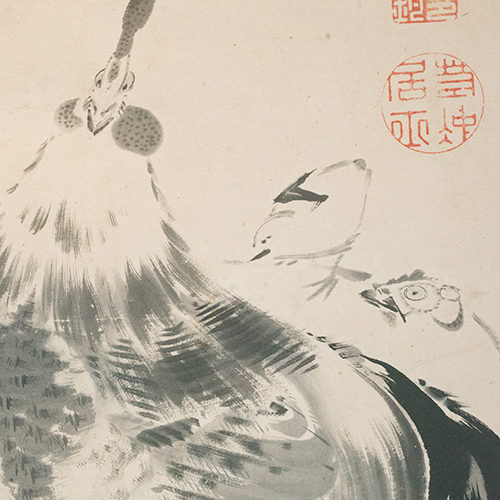

The family business allowed Jakuchu to devote himself to painting, and he devoted himself to sketching plants and animals. We can say that his famous painting of chickens is the result of this attitude. Jakuchu sketched various animals, but peacocks and parrots were not something he could see regularly, so he kept dozens of chickens and spent years studying their shapes and movements. From there, Jakuchu expanded his subject matter to various animals and plants, so chickens must have been an animal that he was very attached to.

Click here to see Jakuchu’s works for sale☜

Jakuchu’s confidence and Dosyokusai-e

Jakuchu, who began with his early paintings influenced by the Kano school and Chinese painting, and later became more and more convinced of his artistic talent as he produced masterpieces, left the following words, according to the Daiten, “I am not a painter, but a painter. According to Taisho, Jakuchu left the following words, which may be an objection to the public’s evaluation of him, who thought he was an eccentric.

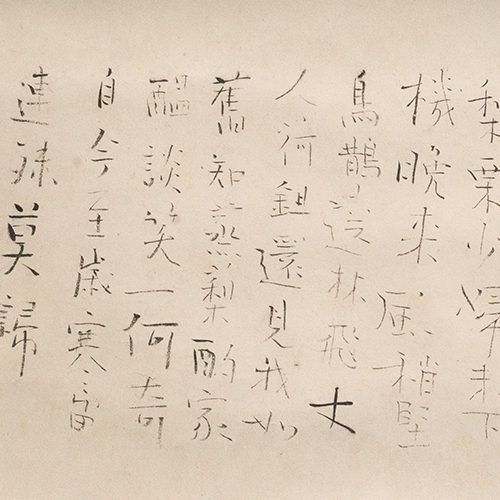

Modern so-called paintings are nothing more than pictures of pictures, and I have yet to see one that is able to depict an object well. Moreover, they are only trying to sell their works by their technique, and there has never been anything that has reached the realm beyond technique. If I am more unusual than others, it is only because of that. (From “Toukei-waganoki”)

Jakuchu emphasizes the importance of “painting things well”. This confident statement must have come from his thorough sketching and observation of animals and plants. Jakuchu’s chickens are very lively, and he probably wanted to emphasize that this is the result of his thorough observation of the animals.

Jakuchu thus gained confidence as a painter, and when he was in his early 40s, he started to create his masterpiece, 30 festskis of Dosyokusai-e.

Click here to see Jakuchu’s works for sale☜

Dosyokusai-e are color paintings depicting animals and plants such as chickens, cranes, peacocks, parrots, plums, chrysanthemums, etc. Jakuchu did not sell these paintings but donated them to his friend Shokokuji Temple in order to preserve them for future generations. The art historian Yasuhiro Sato has also proposed a theory that the reason why Jakuchu donated the festskritten paintings was to make a memorial service for his late father. Jakuchu’s father, Genzaemon, died when Jakuchu was 23 years old, and on the tablets he dedicated to Shokokuji on the 33rd anniversary of his father’s death, it says that he gave away 30 paintings and 3 statues of the three gods. In other words, it is possible that Jakuchu had something special in mind when he donated 33 paintings to the temple on the 33rd anniversary of his father’s death, as a memorial to him.

It seems that the festskritten festskritten was also important to Jakuchu as a painter, and the letter of donation reads as follows

Since these works were not made with worldly motives, we will donate them to Shokokuji Temple and hope that they will be handed down forever as the temple’s sacred objects.

In other words, Jakuchu donated the festschrift to Shokokuji Temple so that his work would remain forever. Jakuchu said, “I will wait a thousand years for someone who understands the value of my paintings”. It is said that with the completion of this festschrift, Jakuchu’s fame reached its peak, but it seems that he himself felt that his paintings were not yet well understood.

Saving the Nishiki Market from a Crisis

It took a lot of work and years to complete 30 paintings in colors like the festus pictures, but the income from the family business, Masugen, a wholesaler of green goods, guaranteed that it would be completed. However, when Jakuchu was 55 years old, a crisis came to Nishiki Takakura Market, where Masugen was located.

At the urging of the Gojo wholesale market, a fellow competitor, the magistrate’s office issued an injunction against the Nishiki Market. The person who stood up to this crisis of the Nishiki Market was Jakuchu, who was the town elder of Obiyacho, one of the towns that made up the market. Jakuchu had already given up the reigns of his family and retired, but he worked energetically for the Nishiki Market, such as paying 15 pieces of silver to have the injunction withdrawn. However, when the Gojo wholesale market paid the 30 pieces of silver, the injunction against the Nishiki market was once again lifted. During this time, it seems that Jakuchu was bribed with a condition that only Obiyacho, where he worked as a town elder, would be exempted from the injunction, but Jakuchu, who was not interested in anything other than his paintings, was unmoved. In the end, this uproar continued for several years, and finally the Nishiki market was allowed to reopen on the condition that he would pay 35 pieces of silver per year. If it had not been for Jakuchu, Nishiki Market might not be what it is today. Jakuchu’s active involvement for the Nishiki Market conveys a slightly different side of Jakuchu from the one conveyed by the monk Daiten, who disliked contact with the outside world.

Retreat to Fukakusa, Kyoto

It can be said that Jakuchu’s past activities, including the festschrift, were supported by the income from his family business, Masugen. However, when Jakuchu was 73 years old, the Great Fire of Tenmei destroyed most of Kyoto, and he lost his house and workshop. Jakuchu had several houses and workshops, but he decided to retire to the gate of Ishimine-ji Temple in Fukakusa, a little away from the center of Kyoto, where he sold a painting for a ton of rice and spent the rest of his quiet life making five hundred arhat statues at Ishimine-ji Temple under the direction of a stonemason.

References

- Nobuo Tsuji, Jakuchu, Kodansha Academic Library, 2015.

- Hiroyuki Kano, Jakuchu: Meiho Price Collection and Kacho Fugetsu, Takarajimasya, 2015.

- Yasuhiro Sato, Jakuchu’s Biography, Kawade Shobo Shinsha, 2019.

![Kyoto [Gallery-So] for purchase, sale, and appraisal of art works](http://gallery-so.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/so-logo.png)